Sarah Harris Fayerweather.

The Fayerweathers

By Tom Schuch

On this site, George and Sarah Harris Fayerweather raised their family from 1841 to 1855.

In the fall of 1832, Sarah Harris was the first Black student at Prudence Crandall’s Female Boarding School in Canterbury, Connecticut.

Sarah Ann Major Harris was born April 16, 1812, in Norwich to William Monteflora and Sally Prentice Harris. William Harris was of African and French West Indian heritage, possibly from Haiti. He was one of the area’s earliest Black advocates for civil rights and Black suffrage. In 1817, he was among a group of Black Norwich and New London men—including two of Connecticut’s ‘Governors of the Negroes’– who filed petitions protesting taxation without representation in the General Assembly. (In Connecticut, Blacks were required to pay taxes, but were denied the right to vote.) The petition was rejected. Some thirty other similar petitions were filed, and similarly rejected, in Connecticut between 1812 and 1870, when the passage of the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution granted all U.S. citizens the right to vote, regardless of race, color, or previous enslavement.

William Harris also understood the importance of education for the advancement of his race, and he ensured that all his children received schooling. Initially, that meant that the Harris children would all attend the Sabbath School and the district school in their home town of Norwich.

Sally Prentice Harris, Sarah Harris Fayerweather’s mother.

In January 1832, shortly after Prudence Crandall had opened her Canterbury Female Boarding School, William and Sally purchased a farm in Canterbury. The real estate transaction was conducted in Sally Prentice Harris’ name, because of a concern about local resistance to Blacks buying land in Canterbury. Sally Harris was light-complexioned, due to her Native American roots.

William and his son, Charles, were agents for William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. Charles was dating Ann Maria Davis, who was employed as a house servant by Prudence Crandall at the time she started her Academy for white girls in Canterbury in 1832.

Although Ms. Davis was not enrolled in the school, she was reportedly allowed to audit some of the classes. She also shared her copies of The Liberator with Ms. Crandall and introduced her to Sarah Harris.

In September 1832, according to the Windham County Advertiser, Sarah Harris asked: “Miss Crandall, I want to get a little more learning, if possible, enough to teach colored children, and if you will admit me to your school I shall forever be under the greatest obligation to you.”

Miss Crandall initially declined to give an answer, stating she would take time to think about it. But Harris made repeated requests, and was admitted later in the fall of 1832.

Mary Harris Williams (Sarah’s sister).

This caused an immediate furor among the parents of the white students in the school and the Canterbury townspeople. Parents withdrew their daughters from the school, forcing Crandall to briefly close it. After consultations with a number of Black and white abolitionists, including William Lloyd Garrison, Arthur Tappan, Rev. Samuel Cornish, James Forten, Rev. Simeon Jocelyn, Rev. Theodore Wright, and Rev. Jehiel Beman, Crandall re-opened her Academy in April 1833, exclusively serving “Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color,” according to the advertisement she published in The Liberator, in March 1833.

This created another furor in the town: stores refused to sell to the students, churches refused admittance for services, doctors refused to provide medical services. The young girls, who averaged fifteen years old, experienced frequent harassment and taunting whenever they appeared in public.

In response to Crandall opening her school to Black girls, the Connecticut Legislature passed the infamous Black Law of 1833, making it illegal to educate Black children from out of state without permission from the town. Crandall was arrested three times for violating that law, and spent a night in jail. The students testified on her behalf at the trial. Crandall was convicted, but on July 18, 1834, her case was overturned by the Connecticut Supreme court on a technicality. Shortly thereafter, on September 9, 1834, the Canterbury Female Boarding School was attacked by a mob, hurling rocks and brickbats and attempting to burn the school down. For the safety and security of her students, Crandall decided to permanently close the school. She subsequently left Connecticut.

By this time, Sarah Harris had left the school. On November 28, 1833, she married George Fayerweather in a double ring ceremony with her brother Charles Harris and Ann Maria Davis. George Fayerweather was a blacksmith, of Black and Native American heritage, from a family of blacksmiths in Kingston, Rhode Island.

On the morning of September 9, 1834, the very day that the Canterbury mob attacked the school, Sarah gave birth to their first child, whom they named Prudence Crandall Fayerweather. They eventually had eight more children. Two of their other children are also named for famous abolitionists: Charles Frederick Douglass Fayerweather (born in New London in 1845), and William Lloyd Garrison Fayerweather.

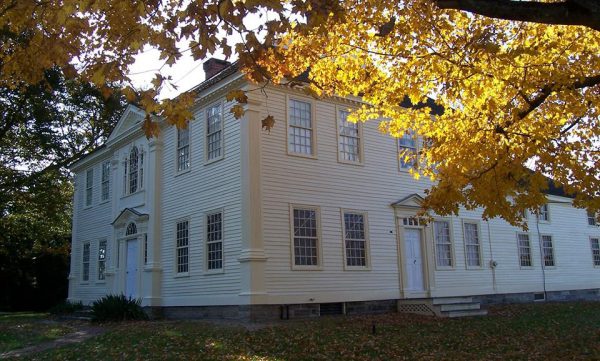

Fayerweather Homestead and Museum, Kingston, RI.

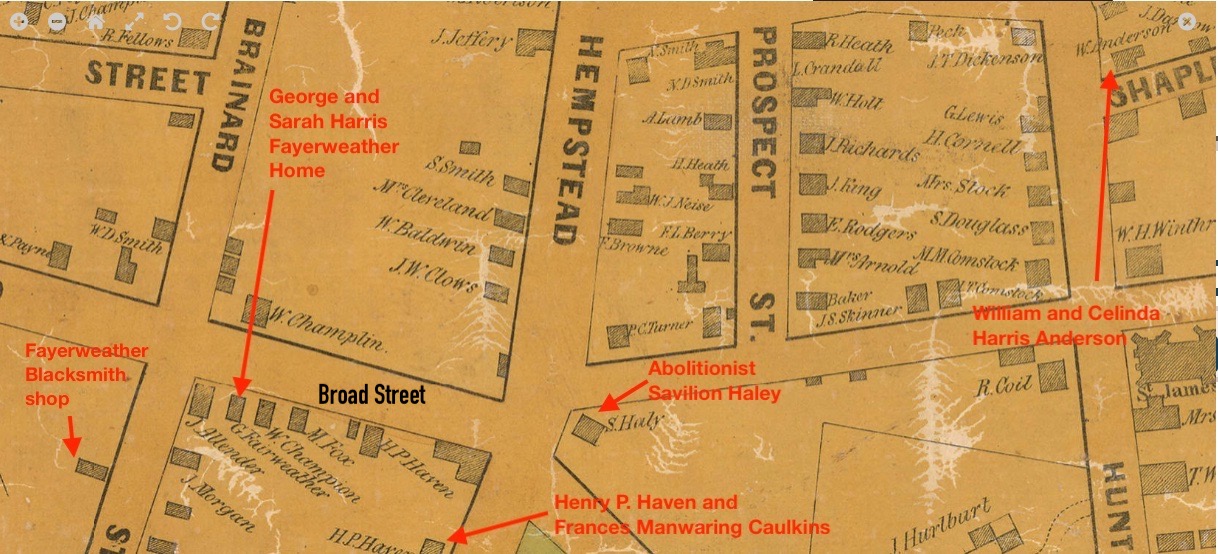

In 1841, George and Sarah moved to the site where 90 Broad Street now stands in New London. George purchased a blacksmith shop around the corner on Brainard Street, near the present-day courthouse.

This was a time of significant turbulence in the nation over abolition, civil rights and education. New London had a dedicated group of both Black and white abolitionists in a town that was largely anti-abolitionist. Although there is scant specific information available on the Fayerweathers’ years in New London, we know that they were both active in civil rights issues, the Abolition movement and the Underground Railroad. George was a New London delegate to the Connecticut Colored Men’s Convention of 1849, as was William Anderson, the husband of Sarah’s sister, Celinda, who lived two blocks away on Shapley Street. The Convention was part of a nationwide movement for enfranchisement and equal rights for Blacks. A third Harris sister, Olive Smith Harris Olney, was married to Frederick Olney, the author of the whaler Merrimac journals. In 1845, Mrs. Olney was conducting a school for thirty Black children in New London. Yet another sister, Mary Harris Williams, had married Pelleman Williams, a teacher who served as Vice-President of that 1849 Convention. Mary had also been a student at Crandall’s School in Canterbury. In 1848, the great abolitionist orator and freedom fighter Frederick Douglass gave four lectures in New London; three weeks later, Connecticut abolished slavery, the last New England state to do so.

Prudence Crandall Museum, Canterbury, CT. Courtesy the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development.

In 1855, the Fayerweathers moved to George’s family homestead in Kingston, Rhode Island. Sarah remained in lifelong contact with Prudence Crandall, was a confidante of Frederick Douglass, and often hosted Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison at their home.

Sarah joined the Kingston Anti-Slavery Society and attended anti-slavery meetings all over New England and New York. She was active in the Kingston Congregational Church and Sunday School.

What was Sarah like? Hallie Q. Brown in Homespun Heroines and Other Women of Distinction gives the following description: “Personally, Mrs. Fayerweather presented with a very distinguished appearance. She was tall, fine-looking, and had a voice of peculiar sweetness. Her favorite attitude was sitting erect with clasped hands, while her steady gaze seemed to pierce far below the surface of things.”

Sarah died November 16, 1878. She is buried near the Fayerweather homestead in Kingston, Rhode Island. Her headstone reads, “Hers was a living example of obedience to faith, devotion to her children, and a tender loving interest in all.”

In 1970, a new dormitory on the nearby campus of the University of Rhode Island was named for Sarah Harris Fayerweather. The Fayerweather homestead is now a small museum and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1984.

Sarah Harris Fayerweather gravestone, Kingston, RI.

Detail from 1850 map of New London.