The Amistad rebellion

By Laura Natusch

When the schooner La Amistad set sail from Havana, Cuba, on June 28,1839, it contained fifty-three shackled Africans–forty-nine men and four children—in its hold.

The Africans had already endured the long journey from the west coast of Africa across the Atlantic Ocean, during which they had been chained together in the dark, unventilated space below deck, with so little headroom that they were unable to stand.

Now they were traveling from Havana to a sugar plantation three hundred miles away. Their captors fed each of them only four potatoes, two plantains and a teacup of water daily. When a few of the men found additional water and drank it without permission, the ship’s crew whipped them and applied a mixture of salt, rum and gun powder to their wounds.

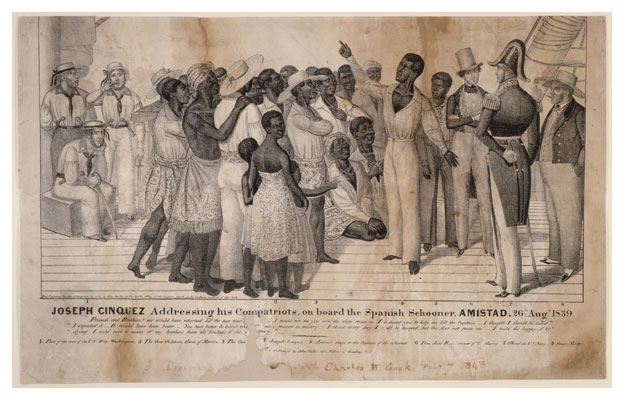

In the pre-dawn hours of July 1, after being told by the cook that they would be murdered and eaten, the Africans fought back. Sengbe Pieh, also known as Joseph Cinqué, used a nail to unlock their neck collars. They then freed themselves from their chains, came above deck, killed the captain and cook, and seized control of the ship.

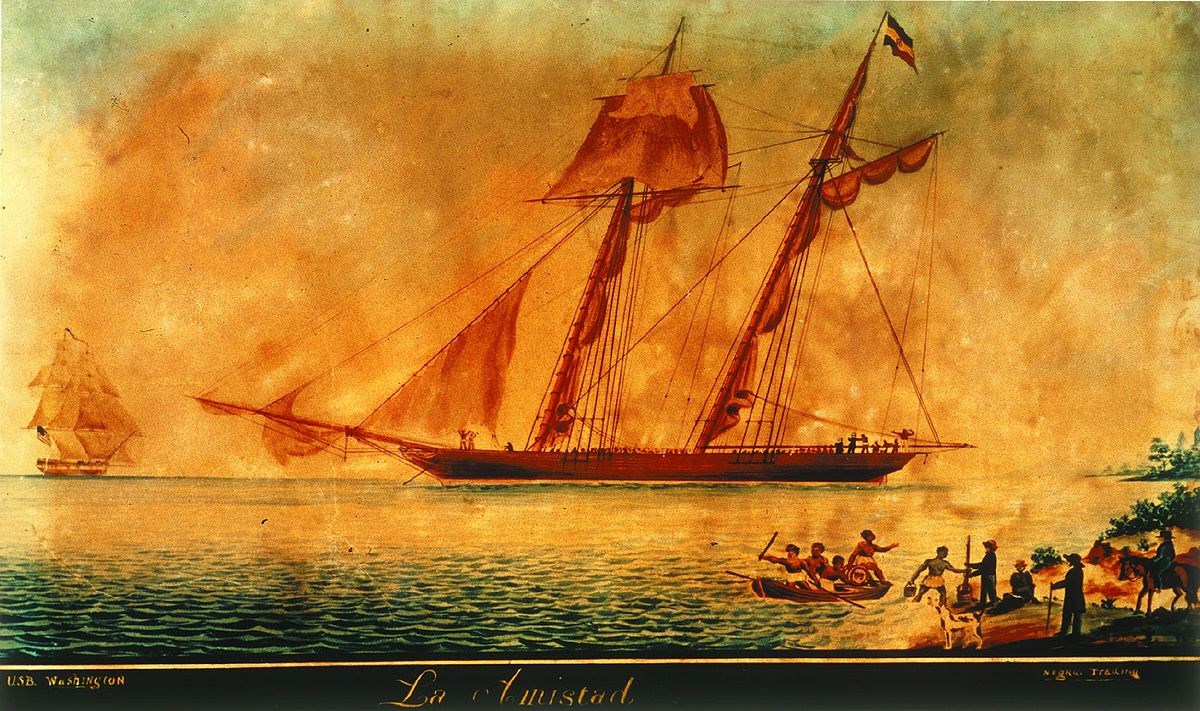

The rebels ordered their would-be enslavers, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, to sail the Amistad to Africa. Montes and Ruiz complied during the day, but unbeknownst to the Africans, they reversed course each night. By late August, the Amistad was off the coast of Long Island.

Lithograph by John Childs.

The Amistad in New London

On August 27, a U. S. Navy survey vessel captured the Amistad and towed her to New London. There, Judge Andrew Judson conducted judicial hearings and ruled that the Amistad rebels should be charged with murder and piracy.

Meanwhile, a New London grocer and abolitionist, Dwight Janes, came on board the Amistad and learned that the insurrectionists had only recently been kidnapped from Africa, in violation of international treaties. He quickly realized that this could form the basis of their legal defense.

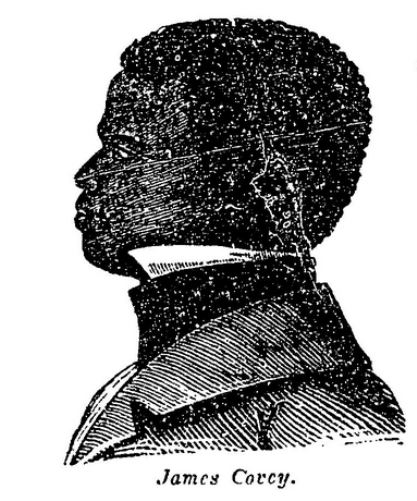

Janes wrote a flurry of letters to other abolitionists who raised funds and found an interpreter, a fourteen-year-old, formerly enslaved sailor named James Benjamin Covey. Covey had been stolen from his parents in Africa when he was five, illegally sold into slavery when he was eight, and rescued by a British Navy vessel. With Covey’s help, the Africans were able to tell their own stories when they appeared again before Judge Judson.

Judson was an unapologetic racist who, as a state legislator, had opposed the education of Black children in Prudence Crandall’s school in Canterbury. Nonetheless, he ruled that the Africans had acted in self-defense when they took control of the Amistad.

At the direction of President Martin Van Buren, who was up for reelection and wanted the support of Southern voters, the federal government appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

United States v. The Amistad

When the case came before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1841, the federal government’s position was that the Amistad survivors had stolen Spanish property, i.e., themselves.

The counterargument, presented by Roger S. Baldwin and former President John Quincy Adams, was that the Africans were free people, not property. Furthermore, because they had already emancipated themselves by the time they arrived in the United States, it would be unconstitutional for the U.S. government to re-enslave them.

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling in favor of the Africans, although it overturned a ruling that the federal government was responsible for transporting them back home.

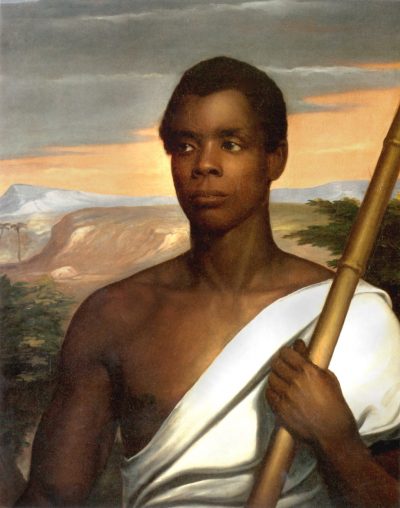

Sengbe Pieh (Joseph Cinqué).

Black Support for the Amistad Survivors

Black communities rallied around the Africans throughout their stay in the United States, sending donations to cover their legal bills and living expenses. Black churches in Cincinnati and Philadelphia donated, as did Black residents of Wilmington, Delaware and Columbus, Ohio. Other Black individuals sent donations as well. A Black cotton broker, Robert Purvis, commissioned a portrait of Cinqué from Nathaniel Jocelyn, selling reproductions and donating the proceeds.

After the Supreme Court ruling, the Amistad survivors raised money for their return to Africa on a speaking tour, charging twenty-five cents a ticket. They often drew their largest and most supportive crowds at Black churches such as the A.M.E. Zion Church on Church and Leonard streets in New York City and the First African Presbyterian church in Philadelphia.

The Rev. James Pennington, the formerly enslaved pastor of Hartford’s Talcott Street Congregational Church (later known as Faith Congregational Church), organized the Union Missionary Society, which raised funds to send two Black missionaries to Sierra Leone with the Amistad survivors.

Return to Africa

Finally, in late November, on the cusp of what would have been the Africans’ third New England winter, the Amistad survivors, accompanied by their former interpreter James Benjamin Covey and five missionaries, set sail for Africa. They arrived in Sierra Leone in January 1842. Thirteen of the Africans, including the three girls, stayed with the missionaries. Within a few months, the rest had begun to live on their own, sometimes returning to the mission when they needed work or support.

Oil painting of the Amistad off the coast of Long Island. New Haven Museum.

Additional Reading

- Amistad & Abolition. Custom House Maritime Museum. Amistad—Abolition (nlmaritimesociety.org).

- Rediker, Marcus. The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom. New York, Penguin Books, 2012.