Shiloh Baptist Church 1963.

Shiloh Baptist Church

By Laura Natusch

“The Black Church was the cultural cauldron that Black people created to combat a system designed in every way to crush their spirit . . . And the culture they created was sublime, awesome, majestic, lofty, glorious, and at all points subversive of the larger culture of enslavement that sought to destroy their humanity.” Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The Black Church: This is Our Story; This is Our Song

“When you pray, move your feet.” – West African proverb

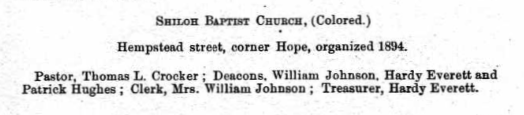

In 1895, when Shiloh Baptist Church first showed up in a New London city directory, the word “colored” appeared after its name. It was the first time the city’s directories had specified the race of a church’s congregants. Five years later, Shiloh became the first Black church in New London to incorporate.

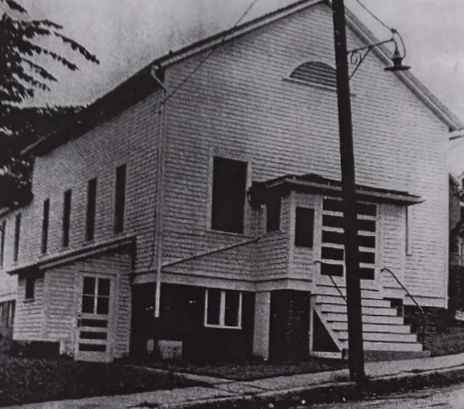

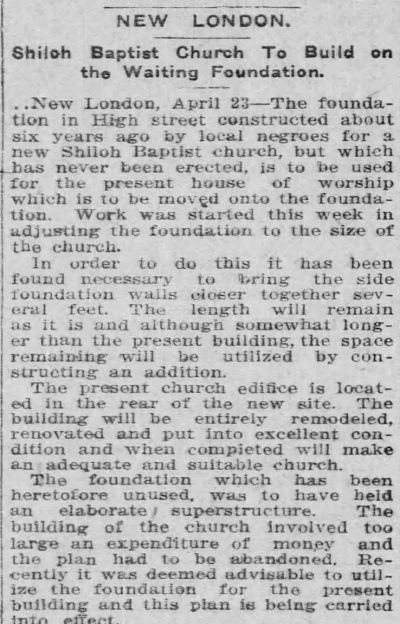

Shiloh’s formation required decades of persistence. As early as 1880, worshippers began gathering in storefronts and private homes, including Rudd’s Feed Store at 123-131 Bank Street, in 66 Hempstead Street and in a former tannery at the corner of Hempstead Street and High Street (now Garvin Street). Shortly after the church’s founding, a fire forced congregants to relocate again, this time to Green Street, where they remained until Elizabeth Batiste purchased a property on High Street for Shiloh’s church.[1] In 1905, New London’s Black freemasons laid a cornerstone for Shiloh’s church on High Street in a ceremony attended by Mayor Bryan Mahan. In 1913, six years after building a foundation for a larger church, Shiloh scrapped its construction plans for financial reasons and decided to relocate its existing edifice onto the foundation instead.

What motivated Shiloh’s congregants to work so hard to build a Black church of their own?

Even in the colonial era, some Black New Londoners were able to attend some primarily white churches. In 1738, for example, an enslaved woman named Phillis and three enslaved children were baptized by their enslaver, Reverend Eliphalet Adams, in New London’s First Church of Christ.[2]

But Black and white congregants were not treated equally. Church seating was segregated, and only white congregants were permitted to vote on church matters.

In the 19th century, prejudice deepened in Connecticut and became codified into law.[3] In 1818, Connecticut’s new constitution specified that only white men were eligible to vote. In the 1830s, when Prudence Crandall opened a boarding school for Black girls, the state responded by prohibiting the teaching of Black students from out of state without a town’s permission, and a violent mob forced her school’s closure. New London excluded Black children from its district schools.

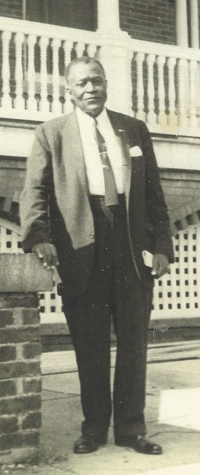

Rev. Albert A. Garvin, Sr. 1959. Photo courtesy Aneesah Ahmad.

Prejudice deepened in New London’s churches, too. Or maybe, as slavery in Connecticut gradually ended and its free Black population grew, a long-standing prejudice was revealed. New London’s abolitionists grew disgusted with local clergy for refusing to renounce slavery. “I know you excuse yourselves by saying this Abolition question destroys churches; breaks them up,” wrote Savillion Haley in the October 19, 1842 edition of The Ultimatum. “. . . if introducing Abolition into the church will break it up, then it is not founded on the Rock Christ Jesus. There is rottenness among you; at the bottom.”

Perhaps, then, rather than asking what motivated Shiloh congregants to build a Black church, a better question might be, “Why didn’t it happen earlier?”

Part of the answer is financial. New London’s Black population in the 19th century was relatively small, making it difficult to raise the money to start or sustain a new church. Shiloh’s founders had more determination than wealth: one deacon listed in the 1895 city directory was a janitor in his twenties; another a coachman in his mid-thirties.

Another part of the answer lies in the census records: at least two of Shiloh’s first deacons, as well as its first pastor, Thomas L. Crocker, were all born in Virginia. Not only were 80% of Virginia’s Black residents Baptists, but they had a long tradition of worshipping in their own Black churches and plantation praise houses.[4] They knew the power of independent Black churches, which combined spiritual uplift with racial self-reliance in a way not possible in churches with white leadership. They brought that knowledge with them as they escaped the violence, disenfranchisement, disillusionment, and poverty that Black Americans faced in the Jim Crow South.

In New London, the Black population continued to grow in the 20th century as rural southern Black families migrated to northern cities looking for work. Linwood Bland, Jr., whose family moved to New London when he was a child, recalled in his memoir A View from the Sixties: The Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut, how Shiloh and other Black churches created nurturing spaces for Black youth: “We walked right out of our church in North Carolina, right into Shiloh Baptist Church. We were in attendance at Shiloh every Sunday. And we attended summer school at the church, also. The summer events were made up of games and other recreational activities, plus refresher school subjects. The school subjects were various, but, as a rule, the summer would almost invariably end with a spelling bee.”[5]

In the 1930s, Shiloh boosted its congregants’ pride in Black achievement with annual Black History Week events organized by Rev. David. W. Moss.[6]

Shiloh’s next pastor, Rev. Albert A. Garvin, Sr., worked tirelessly to meet Black New Londoners’ physical, economic, social and spiritual needs. Sara Chaney described his impact in a 2019 oral history interview: “I do believe that the activity of Reverend Garvin and the local ministers at that particular time had a lot to do with changes that came about in this city. Pfizer’s, through Reverend Garvin’s work, Pfizer’s hired minorities. The telephone company hired minorities. And wherever Reverend Garvin could push, he did.”

Rev. Garvin was so well-respected that in 1943, New London’s Democratic Party nominated him to run for Board of Education, making him New London’s first Black candidate for elected office.

In another sign of the community’s respect for Rev. Garvin, when he offered $6000 for the former New London jail to accommodate Shiloh’s expanding congregation, other potential buyers opted not to outbid him.[7] Shiloh purchased the building in 1958, renovated it, and began holding services there in 1962.

In the 21st century, under the leadership of Bishop Benjamin Watts, Shiloh Baptist Church continues to meet both its congregants’ and its community’s needs. In addition to offering worship services and bible study, it operates a preschool, offers scholarships, develops and showcases musical talent, and hosts both an annual Community Prison Awareness and Prevention gathering and the annual Martin Luther King Day service.

[1] This information comes from Shiloh Baptist Church’s 73rd anniversary program. Elizabeth Batiste may have been Elizabeth Batisse, who lived on Hempstead Street according to New London city directories, as there was no Elizabeth Batiste living in New London at that time.

[2] Richard J. Boles, Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Segregated Churches in the American North. (New York: New York University Press: 2020), 12-13.

[3] Ibid., 197.

[4] William E. Montgomery, “African American Churches in Virginia (1865–1900”), African American Churches in Virginia (1865–1900) – Encyclopedia Virginia

[5] Linwood Bland, Jr. A View from the Sixties: The Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut. (New London: New London County Historical Society, Inc.: 2001), 11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Sten Spinella (2019, November 17). “Shiloh Baptist Church Celebrates 125th Anniversary.” The Day, The Day – Shiloh Baptist Church celebrates 125th anniversary – News from southeastern Connecticut

Church edifice prior to 1950. Photo courtesy of Debra Phillips.

Shiloh Baptist Church’s listing in the 1895 New London City Directory.

Shiloh Baptist Church to Build on Waiting Foundation Norwich Bulletin April 24, 1913.