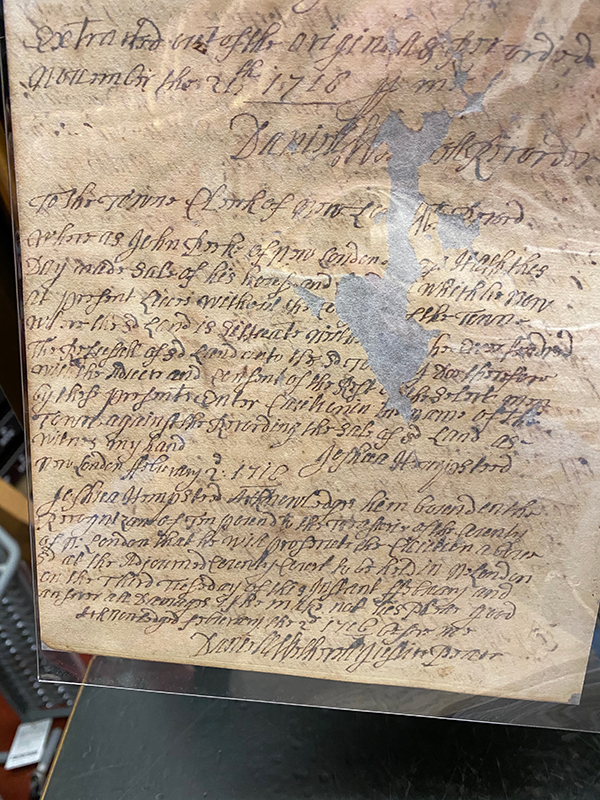

Caution against John Pike regarding selling his land to Robert Jacklin filed by Joshua Hempstead.

Robert Jacklin

By Tom Schuch

The story of Robert Jacklin provides a window into the struggles and challenges that people of color faced in New London in the early 18th century. It is a pioneering story of enslavement and emancipation, of freedom and oppression, of strength and resilience in the face of organized racist opposition, and ultimately of soldiering on against formidable odds.

Robert Jacklin was enslaved for over twenty years in the family of Dr. Peter Tappan of Newbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony. Jacklin was able to save enough money, apparently by working side jobs, to purchase his own freedom on October 15, 1711. He was granted a pass, required at the time, which would allow him to travel to New Jersey ”unmolested.” A year later, however, he was living in New London where, on October 9, 1712, he married Mary Wright, the daughter of William and Hagar Wright.

Hagar was a Black woman enslaved to James Rogers; William was a Native American who agreed to serve a six-year indenture to Rogers to earn freedom for both himself and his wife. They were part of New London’s Rogerene sect, religious dissidents who regularly disrupted services of the government-sanctioned Congregational Church. Wright and Rogers had both been jailed repeatedly for these activities, and William was eventually banished from New London.

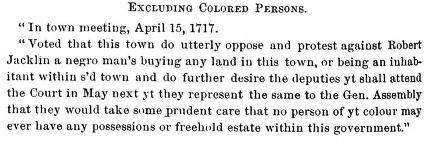

Robert’s first wife Mary had died in 1713, shortly after childbirth, and he married Hagar about 6 months later. He was industrious, and as their family began to grow with the birth of two sons, he purchased a twelve-acre farm, known as Pike’s Lot, or Pike’s Hollow, from John Pike on February 2, 1717. This farm was located along the Colchester Road, below Post Hill, on what we now know as Vauxhall Street. This purchase generated an immediate backlash from the New London voters, known as Freemen. Joshua Hempsted, the noted diarist, a Townsman or Selectman at the time, wrote the following in his Diary on the very day of the sale: “I entered a caution against ye Sale of Jno Peeks house and land.” That caution against John Pike (Jno Peeks) is entered into the official land records of the town of New London. The Freemen then called a town meeting on April 15, 1717, and “voted that this town do utterly oppose and protest against Robert Jacklin a negro man’s buying any land in this town, or being an inhabitant within s’d town and do further desire the deputies yt shall attend the Court in May next yt they represent the same to the Gen. Assembly that they would take some prudent care that no person of yt color may ever have any possessions or freehold estate within this government.”

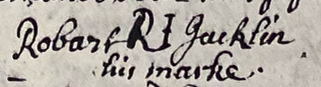

Robert Jacklin’s “mark” in lieu of his signature, indicating that he was probably illiterate.

This action is one of the first blatantly racist actions taken by a Connecticut town. In addition, there was a fraudulent effort to re-enslave him, which he overcame by producing his emancipation papers. But by this time, Connecticut had already enacted a series of laws that restricted the freedom, rights and even movement of Blacks and Native Americans. For example, in 1643, three years before New London was founded, the colony had joined in the Articles of Confederation of the New England Colonies, which included a Fugitive Act, applicable to indentured servants and slaves. In 1690, Blacks and Native Americans were forbidden to be on the streets after 9:00 p.m., and they were required to carry a pass to travel beyond their designated area. In 1708, any Black who disturbed the peace or attempted to strike a white person would receive thirty lashes. A law enacted in 1730 authorized a punishment of forty lashes for any Black, Native American or multi-racial person who uttered or published anything that, if said by a white person, would be actionable. Other laws were passed in 1702 and again in 1711 to prevent slaveholders from dumping their slaves when they become old or enfeebled by freeing them. These laws were inconsistently enforced, and were generally designed as harassment, creating an atmosphere of precarious existence for Blacks, discouraging their settlement and increasing their dependence on the toleration of the white majority. The action taken by the Freemen of New London against Robert Jacklin was a clear example of this bigotry. Although the sale of Pike’s farm occurred in 1717, the deed was not recorded until March 22, 1718. It is unknown whether the action of the town was a factor in this delay.

Account of vote taken April 15, 1717 in New London.

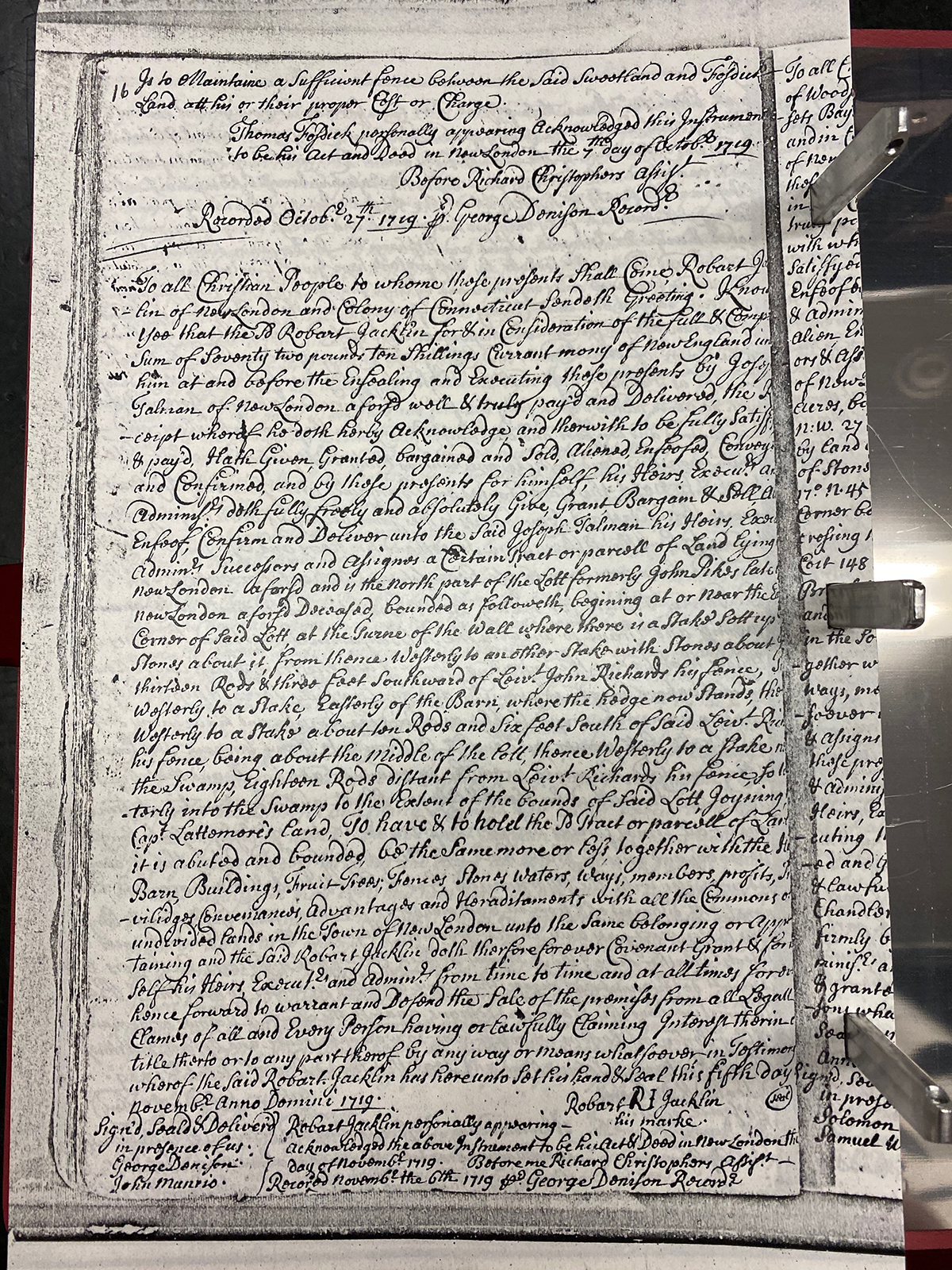

In spite of the strong opposition, Robert Jacklin did purchase the farm. But his existence in New London was not an easy one. He is listed in thirty legal cases in New London County Court as either a debtor or a creditor. He is the defendant in three quarters of those cases, an indication of the difficulty he had in paying his bills. Many of those cases were eventually dismissed, possibly because they were settled out of court. We do not know the source of his financial difficulties, whether it was drought, illness, and even some form of racial harassment. He was able to sell that farm for a profit in November 1719 and subsequently leased a farm in New London’s North Parish (Montville) from Jonathan Rogers, also a member of the Rogerene sect, which was sympathetic to the plight of Blacks and Native Americans.

In 1728, Jacklin and his third wife, Zipporah, purchased a 128-acre farm near Gardner’s Lake in the Salem section of Colchester, where they became the first Black landowners in that town. In 1729, they sold that farm and moved to Norwalk. They purchased a farm in what is now New Canaan in 1735 and remained there to raise their family. At least three of Robert Jacklin’s descendants went on to fight for American independence in the Revolutionary War.

Deed of sale Robert Jacklin to Joseph Talman 5 November 1719.