Preston Hamilton

By Laura Natusch

Preston Hamilton purchased property behind the Crocker House, making it available to the public as Hamilton Park until his death. Indian Progress, September 4, 1879.

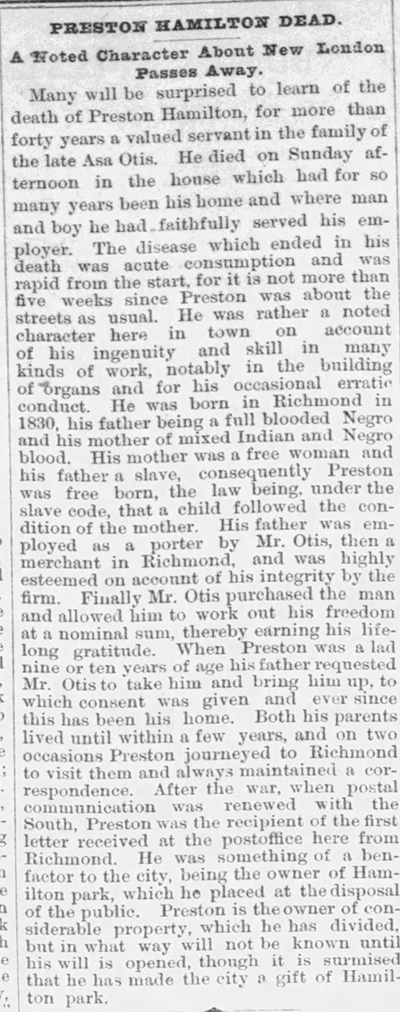

Preston Hamilton was born in 1830 in Richmond, Virginia. His mother was a free woman of Native American and Black ancestry. His father was enslaved until Asa Otis, a merchant who had moved to Virginia from New London, purchased him and allowed him to work off his freedom for a nominal fee.1 According to his obituary, Hamilton inherited his mother’s status as a free person and was never enslaved.

When Otis retired and moved back to New London, Hamilton’s parents asked Otis to bring Hamilton with him. The 1840 census shows ten-year-old Hamilton living in New London with Otis and his family. He continued to live in the Otis house on the corner of Union and Golden streets for the rest of his life.

As a young adult, Hamilton spent much of his spare time at the nearby T.M. Allyn piano and melodeon factory, using Allyn’s tools and learning instrument building and fine cabinetry. 2 In 1853, the factory burned. Hamilton painted a watercolor of the conflagration, which would have been visible to him from his home.3

Preston Hamilton’ obituary, published in The Day, December 12, 1881.

On May 26, 1866, a brief notice ran in the Hartford Courant: “Mr. Preston Hamilton, of New London, has contracted to build an organ for parties in Boston at a cost of $2000. The Bulletin says: “Mr. Hamilton is what may be called a natural genius. He never served an apprenticeship at any mechanical branch of industry, but furnished with the proper tools he can make almost anything.”4

$2000 was a lot of money in 1866. In 1870, the average annual earnings for a U.S. manufacturer was only $378.5 Hamilton must have been extraordinarily skilled to command such a price for his work.

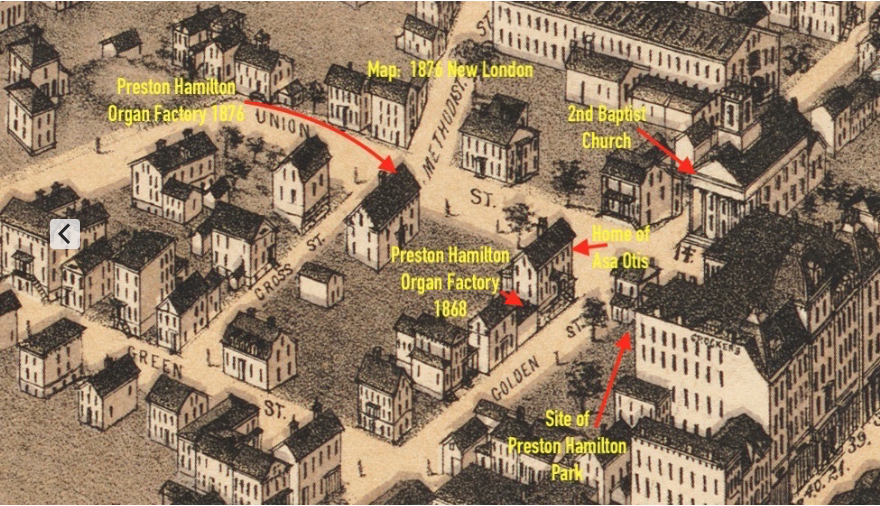

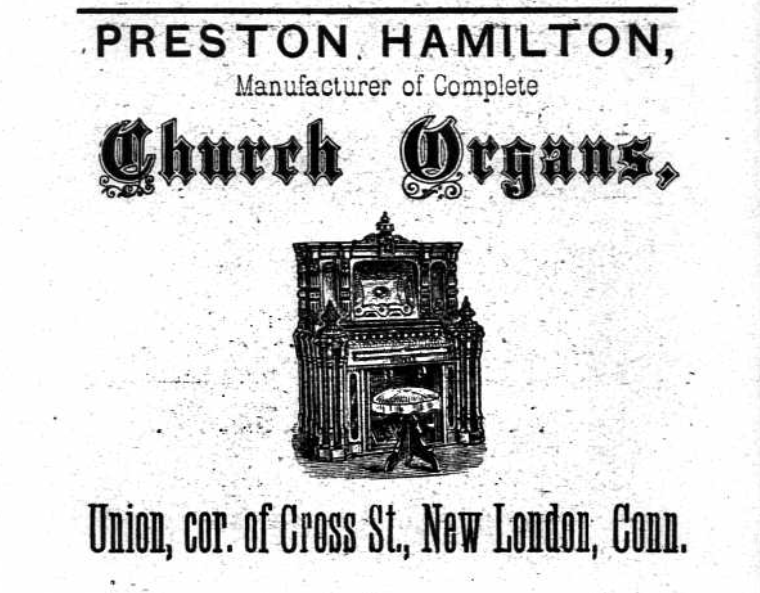

Hamilton’s organ business grew over the next decade. An 1868 map of New London shows a small building next to the Otis house labelled P. Hamilton Organ Factory. The 1870 census listed Hamilton’s occupation as “organ builder.” (His occupation wasn’t listed in previous census records.) In 1876, he placed an advertisement as a manufacturer of church organs in the New London City Directory, and a map of the same year shows that he had moved his factory to a larger building.

Circa 1880, the nationally acclaimed organist William H. Bush got his professional start as a boy playing a Preston Hamilton organ at the Second Baptist Church.6 In 1911, The Day ran a poem about a forty-year-old church organ built by Hamilton:

“…A monument of thanks to God he planned,

A fitting tribute from a grateful heart,

That God had placed him in a pleasant land,

And here among kind friends had cast his lot.

Carefully then he chose each separate unit,

Slowly fashioned them with greatest skill,

Until at last, behold, “a perfect organ—

‘Twas purchased by our church upon a hill…”7

But Hamilton wasn’t recognized solely for his organ making skill. According to columnist R.B. Wall, writing in 1926 for The Day, he owned property and was known as a good landlord. 8

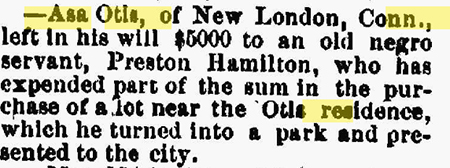

When Asa Otis–with whom Hamilton had lived since childhood–died in 1879 at the age of ninety-three, he was both New London’s oldest and wealthiest resident.9 In his will, he left Hamilton $5000.10 Hamilton used some of that money to purchase the E.F. Dutton house across the street from the Otis house, where the Crocker House Annex now stands. He either razed or moved this house, then made the lot available to the public as Hamilton Park11 until he died of consumption (tuberculosis) in 1881.12

Hamilton traveled to Virginia several times to see his parents before their deaths,13 and his will specified that $1000 be divided among his seven siblings. But he seems to have felt at least as strong a connection to the Otis family: he left the majority of his estate, including Hamilton Park, to Asa Otis’s niece Mary Hunt,14 and he is buried with the Otis family in Cedar Grove Cemetery.

Preston Hamilton’s painting of the fire on Union Street at T.M. Allyn’s piano factory_image courtesy of the Public Library of New London.

1876 map with Preston Hamilton sites labelled.

Preston Hamilton ad in the 1876 city directory, pg 15.

1 “Preston Hamilton Dead: A Noted Character About New London Passes Away.” New London Day, December 12, 1881, p.4.

2 “Masonic Building For New London: Union Lodge to Build on Site of Former Organ Factory Operated By Preston Hamilton—Moving Buildings Through Streets—Contest Over Democratic Nomination for Sheriff.” Norwich Bulletin, September 26, 1914, p.12.

3 Pearson, Dan. “Slavery to civil rights theme of exhibit on blacks in southeastern Connecticut.” The Day, November 30, 1998, p.9.

4 “State Matters: Miscellaneous.” Hartford Courant, May 26, 1866, p.2.

5 Long, C.D. Wages and Earnings in the United States, 1860-1890. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1960), 41.

6 “William H. Bush Quits as Organist of First Baptist.” The Day, August 31, 1929, p.18.

7 “The Passing of the Organ.” The Day, August 24, 1911, p.8.

8Wall, R. B. “Golden St. Garage Site Near Livery Stable Mart Popular in Last Century.” New London Day, March 20, 1926, p.3.

9Cedartown Advertiser, September 25, 1879, p1. https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn88054032/1879-09-25/ed-1/seq-1/

10 “News of the State.” The Meriden Daily Republican, March 13, 1879, p.1.

11 Wall, R.B. “Early History of Southern Section of Union Street.” New London Day, November 3, 1914, p.4.

12 “Preston Hamilton Dead.” New London Day, p.4.

13 Ibid.

14 “A Will That Won’t.” New London Day. December 17, 1881, p4.