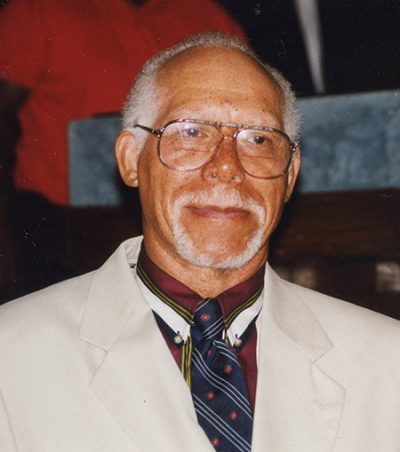

Linwood Bland, Jr.

Photo courtesy Lonnie Braxton II.

Linwood W. Bland Jr.

December 21, 1926 — March 15, 2005

By Lonnie Braxton II

Son, brother, father; student, farm hand, laborer, baseball player, sailor; World War II and Korean War veteran; auto mechanic, electronics technician, shipyard machinist; civil rights activist, New London NAACP chapter president; historian and author. Linwood Bland, Jr., was all of those things.

Linwood Jr. was born December 21, 1926, in Weldon, (Halifax) North Carolina, the third of four children of Linwood Bland, Sr., and Nannie Bland. In 1928 young Linwood was living with his father, mother, three siblings (Ervin, Rose, and Major), and his great-grandmother Leah Carnegie on Poplar Street in Weldon, NC. (Per the 1930 United States Census, Leah Carnegie’s date of birth was 1857, which would mean she was born enslaved.)

23 Franklin Street. New London Landmarks.

In 1929, Linwood Bland, Sr., left Weldon, North Carolina for New London, Connecticut to play baseball for a local Black baseball team, the New London Colored Giants, and work at the Mohegan Hotel. On June 4, 1935, Linwood, Jr. and his siblings joined him in New London; the family address was 73 Hempstead. For several years Linwood, Jr. attended the former Saltonstall School. From Hempstead Street the family moved to 9 Stony Hill (a street now lost to urban renewal), where they remained for thirteen years.

In 1944, as an 18-year-old, Linwood Jr. was living on his own, working at the New London Submarine Base, and was registered for the draft. During WWII, he served in the U. S. Navy. There is no record of his graduating from New London High School. On April 28, 1960, he was living on Mather Court. According to the New London Day, one of his tenants, Ms. Isabell McClure, and Mr. Enoch Marshall picketed the local Woolworth’s on State Street.

In 1965, Mr. Bland purchased the house at 23 Franklin Street, where he resided until he passed on March 15, 2005. Thus, this was his address during most of his activism.

After serving in two wars, Mr. Bland returned to New London with the expectation of working and getting on with his life, but the injustices he continued to see would not allow him that luxury. He witnessed and felt the pain of so many, like those who worked at Electric Boat during the war but were fired and not rehired after it: “After the war, EB acted like those people didn’t have to eat.”

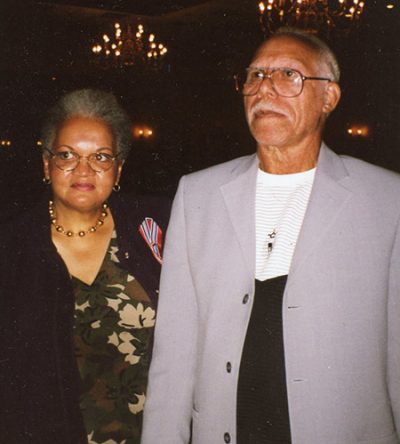

Linwood Bland, Jr. and Sara Chaney. Photo courtesy Lonnie Braxton II.

Despite the passage of Fair Housing laws, Blacks often had trouble obtaining decent housing. According to the New London Day (July 8th and 9th 1942), Mr. William E. Taylor, a Black Electric Boat shipyard worker, had his New London home condemned as unfit for human habitation; nevertheless, he was denied Groton housing built for shipyard workers.

Discrimination in employment or housing and other apparent civil rights violations were Mr. Bland’s call to action. And for over sixty years he never fail to answer the call. As president of the New London NAACP, he pushed to ensure that residents displaced by urban renewal would have affordable, high quality housing. He fought on behalf of Black men and women who were denied jobs or promotions because of their race. His memoir, A View from the Sixties: the Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut, not only details his own and his contemporaries’ strategies and achievements during the civil rights movement, but also provides a window into the lives of Black New Londoners throughout the early and mid-twentieth century: the migration of Black southern families into the city, Black fraternal and civil rights organizations, Black churches, and even Black sports teams. He trained a generation of activists, many of whom went on to not only continue his work but to train and inspire other to take up the cause. His legacy survives him.

Bland (center) at the New London NAACP Black History program, 1963. Photo courtesy Aneeesah Ahmad.