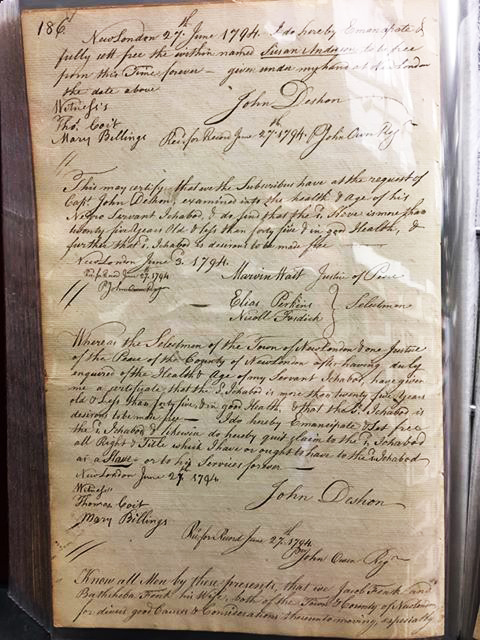

Ichabod Pease Emancipation paper June 27, 1794

Ichabod Pease

By Tom Schuch

Heroes come from all walks of life, and often from humble beginnings. But when their moment of destiny arrives, they are ready and rise to the challenge. Some heroes achieve immediate fame and renown, but other heroes may go unrecognized until some quirk of fate reveals their story. Such is the case of a New London hero, Ichabod Pease. His heroism was recognized briefly at the time, but then was largely forgotten, or overlooked, for over one hundred and eighty years. In 1837, Ichabod Pease showed us a model of strength, determination and resilience in the face of racism and oppression.

Ichabod Pease was born into slavery on Fishers Island in 1755. His lineage is unknown. He spent the first thirty-nine years of his life enslaved in the Mumford household in New London. He learned to read and write, and also learned the shoemaking trade. He married Rose Froud, who was also enslaved, around the time of the outbreak of the American Revolution.

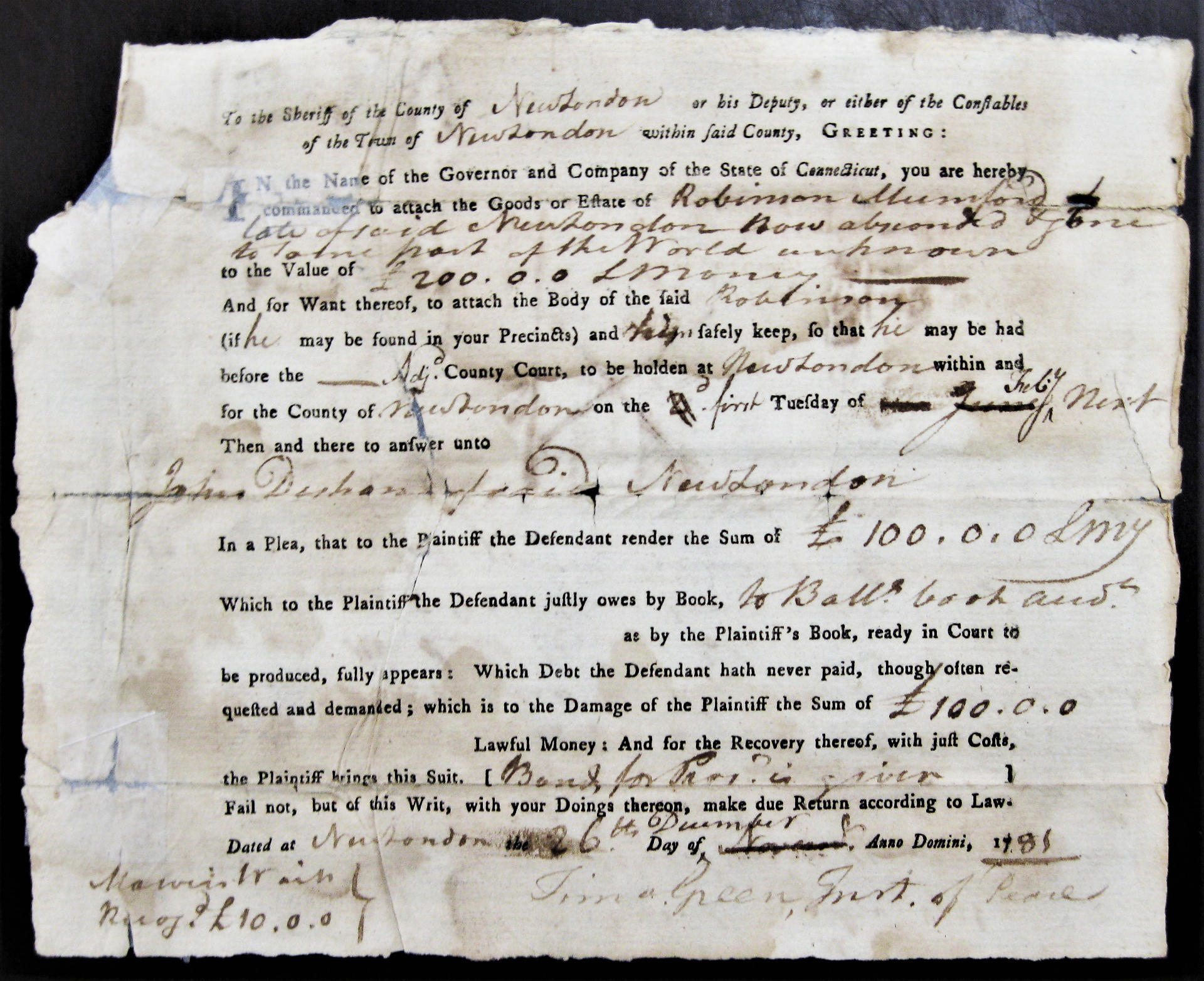

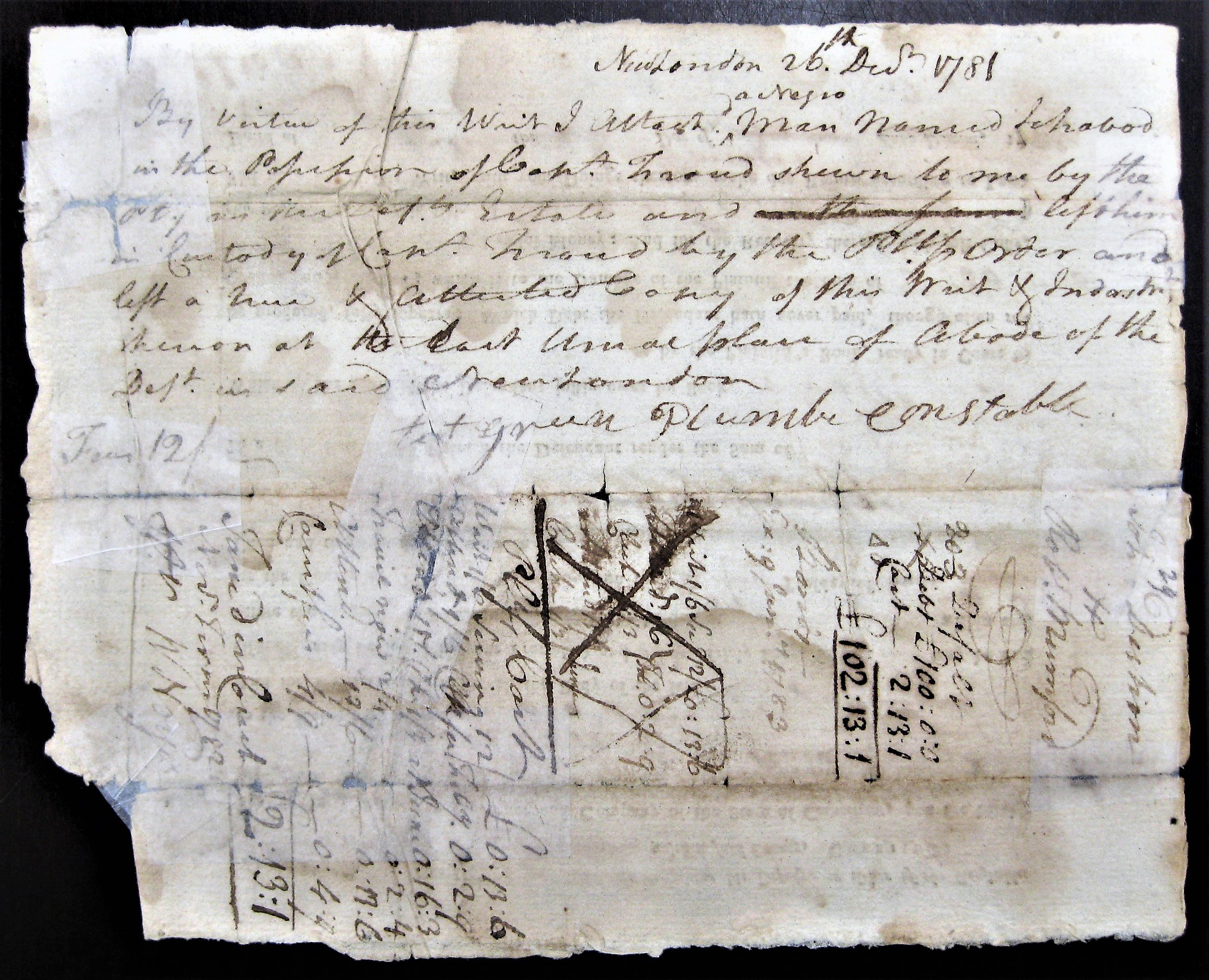

In 1779, his slaveholder, Robinson Mumford, a Loyalist, made plans to move South and take Pease with him, which would have separated him from his wife. Pease resisted, escaped from bondage, and signed aboard a sailing ship. As the ship departed New London, a storm arose, forcing it to return to port. Pease was now a fugitive, in danger of recapture and re-enslavement.

Pease spent the next two years in hiding in New London, probably supporting himself as a shoemaker. He was finally recaptured in December, 1781, three months after Benedict Arnold attacked and burned New London. He was held in the custody of Captain Robert Froud, where his wife Rose was also enslaved, for the next thirteen months while his case wound its way through the court system. In January 1783, he was sold to Captain John Deshon in order to settle an outstanding debt of Mumford’s. He remained enslaved to Deshon for eleven years, finally gaining his freedom by manumission on June 27, 1794.

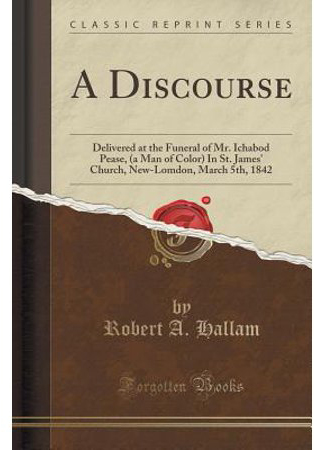

Cover of the Ichabod Pease Discourse (Eulogy) by Rev. Robert Hallam

Rose Pease was manumitted in 1796, and Captain Froud, in recognition of the devoted care she had given him and his wife in their declining years, granted her lifelong use of his house and a small plot of land on Cape Ann Lane (Jefferson Avenue).

The Peases then lived quietly in New London. Ichabod worked as a gardener for General Jedidiah Huntington, formerly of George Washington’s staff, at the Mount Vernon House on Huntington Street, and he was said to resemble the General in manners and character. The Peases were devout parishioners of St. James Episcopal Church.

Sadly, Rose Pease died childless in 1808. Upon Rose’s death, the home they had been living in on Cape Ann Lane was returned to Captain Froud’s heirs.

Ichabod Pease continued to work as a gardener at the Mount Vernon House for Jedediah Huntington and later Joseph Hurlburt, and to attend St. James Episcopal Church. Except for a couple of land transactions circa 1820 with Samuel and Sarah Deshon Wheat, the daughter of Captain Deshon (who was instrumental in obtaining his manumission), there is very little information available for Mr. Pease until his moment of destiny arrived.

By the 1830s the entire nation, including New London, was embroiled in the controversy over the growing abolition movement and the education of people of color. Towns, churches and even families were divided, often heatedly, on the subject. In 1835, New London was strongly anti-abolitionist, and by 1837 this sentiment led to a growing resentment against schooling Black children in classrooms with white students. The New London School Society was vexed over how to resolve the problem.

That is when Ichabod Pease stepped forward. Mr. Pease proposed to start a school for Black children, which he would operate from his home on Church Street (now Governor Winthrop Boulevard).

Before and after shot of restored gravestones of Ichabod and wife, Rose. Cedar Grove Cemetery, New London

He was 81 years old at the time.

His initial proposal was rejected by the New London School Society.

But Mr. Pease was persistent. He made his proposal a second time. This time the proposal was accepted, and he was awarded $50 per year by the School Society to operate his school. So, in 1837, Ichabod Pease established the first school for Black children in New London. He continued to operate it in 1838. In 1839, the Connecticut Legislature changed the law, stating that no child could be excluded from any publicly funded school. It appears that shortly thereafter Black children were assimilated into the regular New London school system. But for two years, Ichabod Pease had provided a solution to the crisis of education for New London’s Black children.

This is the stuff of heroes.

Ichabod Pease died on March 3, 1842 at age 86. At his funeral, “the most eminent citizens sought the privilege of acting as bearers at his funeral,” according to Rector Robert Alexander Hallam’s “Annals of St. James Church New London, for one hundred & fifty years.”

Hallam’s eulogy for Pease, titled “The Dignity of Goodness,” reads, in part:

“We, doubtless, all feel, that this was a remarkable man; the more remarkable, because his distinction was of an uncommon sort, and lay purely in eminence of goodness.

. . . All who beheld him, knew that they looked upon a good man . . . He sought no praise, he courted no attentions. He walked quietly in his own appointed sphere, with a modest unconsciousness of his own superiority, intent only on being faithful, and doing his duty.”

Ichabod Pease stood up on behalf of the children of his community, and in doing so, earned the love and respect of people of all races. He remains an inspiration to us today, as we, too, struggle with issues of equity and justice for all.

1876 map showing Pease’s former home school

Deshon v. Mumford, 1781 Writ, front page Writ regarding Pease’s re-enslavement

Deshon v. Mumford, 1781 Writ, back page Writ regarding Pease’s re-enslavement

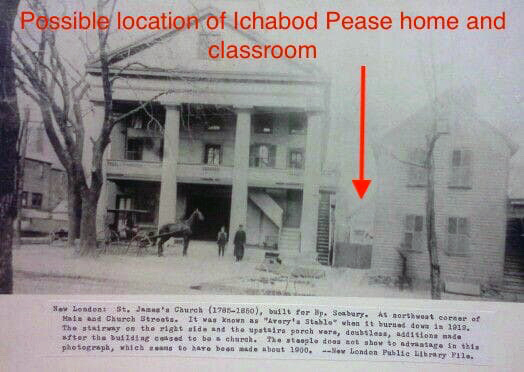

1895 photo showing Pease’s home/school in rear lot

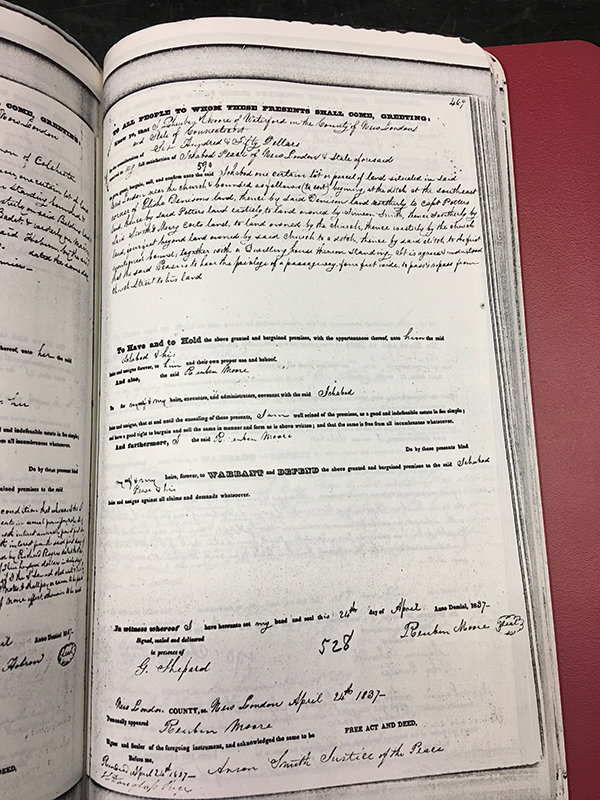

April 1837 Deed of purchase of home/school