Portrait of Frederick Douglass, attributed to Elisha Hammond 1845

Frederick Douglass and Dart’s Hall

By Tom Schuch

On the weekend of May 20-21, 1848, the noted orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass delivered four lectures on this site, at the now-demolished Dart’s Hall. Douglass’ appearance in New London was both timely and significant.

The fierce debate over slavery, civil rights and education for Blacks that engulfed the entire nation had also been raging in New London, dividing her citizens, her churches and even her families. For nearly two hundred years, New London’s economy and prosperity had been inextricably bound together with the economies of the “sugar islands” in what was known as the West Indies Trade. New England’s farms, forests and fisheries were the life-supporting provisioners and enablers of the plantation economies, which were built on the stolen labor of millions of kidnapped, enslaved Africans. Consequently, the abolition movement of the 1830s was seen as a threat to local economic prosperity, and New London was strongly anti-abolitionist.

But by the 1840s, New London was the home of an increasingly outspoken group of abolitionists made up of Black, white and Native American men and women. Notable among them were: two of the Harris sisters, Sarah Fayerweather and Celinda Anderson, former students at Prudence Crandall’s Female Boarding School in Canterbury; their husbands, George and William, respectively, both of whom became New London delegates to the 1849 Connecticut Colored Men’s Convention; two Hempstead sisters, Mary and Martha, and their abolitionist husbands; Lavinia Ruggles Parkhurst and Frances Ruggles, who were sisters of David Ruggles, the founder of the New York Committee of Vigilance who helped hundreds of self-emancipated fugitives, including Frederick Douglass, reach freedom; publisher William Bolles, who in 1843 had published Stephen Sygmund Foster’s scathing attack on the complicity of Christian churches in slavery; and Savillion Haley, who built five houses for free Blacks on Hempstead Street in the mid-1840s. Bolles, Haley and Dwight Janes, all New London residents, had provided key testimony in the Amistad case which led to freedom for the captives, and New London was the home of two anti-slavery newspapers, Ultimatum and The Slave’s Cry.

So by Douglass’ arrival in 1848, New London was fertile ground for the greatest anti-slavery orator of the day.

By his own account in the May 26, 1848, edition of his anti-slavery newspaper The North Star, his first two lectures in New London were thinly attended and the reception was disappointing. Douglass stated that “it is by no means a grateful task to abolitionize Connecticut. As a State, it will probably be the last to be reformed . . . There are noble exceptions to this rule. There are good men and women in this State and in New London, but, as a mass, this representation accords with their character.”

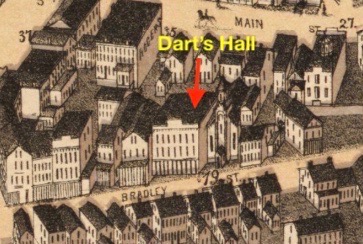

1876 map showing Dart’s Hall on Bradley Street.

However, the reception of his final two lectures was decidedly different: “The last two meetings in New London were an exception to the description. The audience manifested a deeper interest in the subject than I had hitherto seen in any part of Connecticut. I think New London about the best part in the state.”

There are no records of the topic of his four lectures in New London, and there are no records of who was in attendance. The content of those lectures has been lost to history, but there are other records of lectures that he gave elsewhere around that time. He had recently spoken of his opposition to the Colonization Movement of Free Blacks to Africa (“We have Decided to Stay”), of his opposition to slavery in the Nation’s capital, of the complicity of Christian churches in slavery, and of France’s recent emancipation of all slaves. It is likely that his New London lectures were on similar topics.

Douglass himself had recently returned to the United States from England, where he had fled to avoid re-enslavement. His lecture tour in England and Ireland had been a rousing success. A fundraising effort was initiated there during his tour which ultimately enabled him to purchase his freedom. So he returned to the United States a free man. He used his lecture tours to promote his anti-slavery message, often at his personal peril. He had also recently published his autobiography and his brand-new newspaper, The North Star.

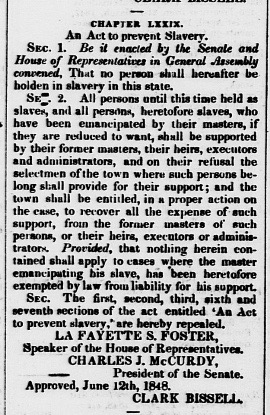

Finally, it is significant that Frederick Douglass appeared in New London on May 20 and 21, 1848. On June 12, 1848, a scant three weeks later, last among the New England states, Connecticut finally abolished slavery, fulfilling Douglass’ prediction.

Connecticut Legislature Abolishes Slavery June 12, 1848.

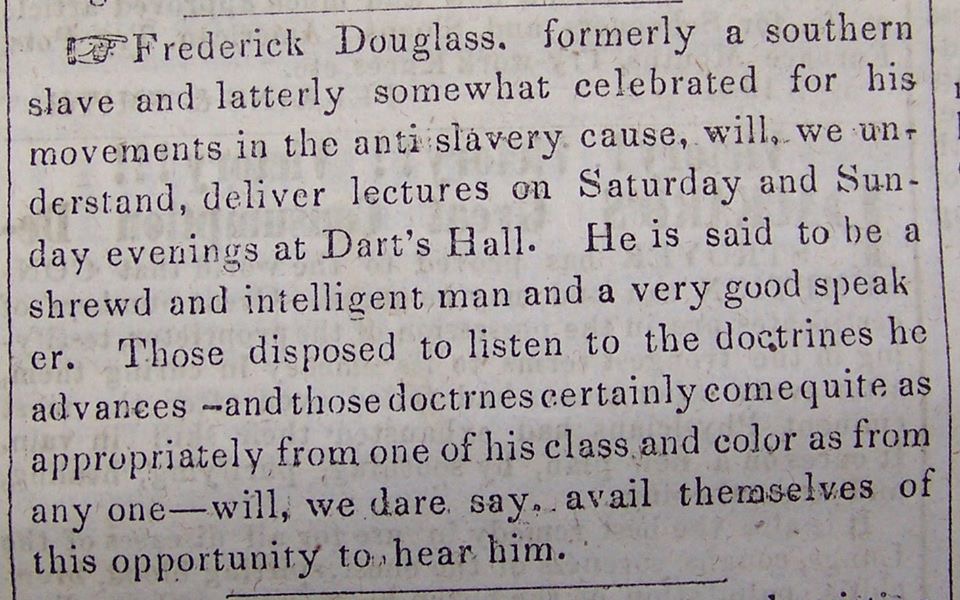

Announcement of Frederick Douglass’ lectures in New London Chronicle, 1848.

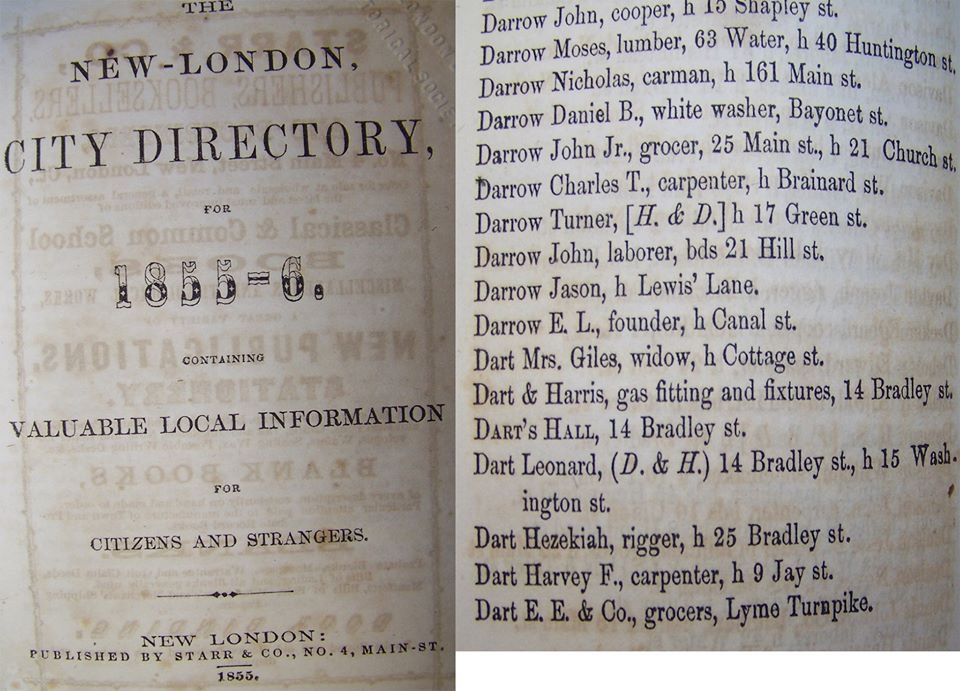

Dart’s Hall in 1855-56 New London Directory.