United Societies Parade Float, James H. Brown standing beside float. Photo courtesy of Paul Duarte.

66 Hempstead Street

By Tom Schuch

This three-and-a-half-story structure at 66 Hempstead Street was originally built in 1866 as an adjunct to a tanning factory located across the street. Over the next one hundred and fifty-five years, however, it served not only as home to a variety of manufacturing businesses, but also as the focal point in the life of the surrounding community.

Also across the street are the Haley houses, built in the early 1840s by Savillion Haley, a white abolitionist, who sold them at cost to free Blacks. This was in the midst of a national—and local—- controversy over Black suffrage, education for Black children and the abolition of slavery.

They were originally purchased by free Black tradesmen, including a mariner, a rigger, a blacksmith, a butcher, a stonemason and a machinist. As more people moved into the area, this became the nucleus of one of New London’s first Black communities. Four of the five Haley houses remain standing today (#73, #77, #81 and #83).

Mid-nineteenth and early twentieth century residents included John and Lavinia Ruggles Parkhurst, (the sister of David Ruggles, the noted Freedom fighter, conductor on the Underground Railroad, and founder of the New York Committee of Vigilance); John and Lavinia’s grandson, William Herbert Bush, a nationally famous organist and music teacher; Sadie Dillon Harrison, the Secretary of the United Negro Welfare Council, who, with Edwin Hackley, wrote and published the Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers, the first travel guide catering to the needs of Black travelers. Former New London NAACP President Linwood Bland, Jr and civil rights pioneer Sara Chaney both lived across the street from 66 Hempstead Street when they were children.

66 Hempstead Street in 2020.

The factory at 66 Hempstead Street provided employment for members of the surrounding community. Residents initially worked there in the tannery, and later in the cane umbrella and silk factories that took the tannery’s place. During a manufacturing downturn in the early 1880s, the building assumed a different and more significant role: what had been a factory became a community social center, dance hall and storefront church serving the needs of the developing neighborhood. That storefront church later became established as Shiloh Baptist Church, the first Black church in New London.

By 1894, 66 Hempstead again reverted to factory use. Shiloh Baptist Church built its first dedicated house of worship at 23 High Street (now Garvin Street), abutting the backyards of the Haley houses on Hempstead Street.

In 1914, the factory finally vacated the structure at 66 Hempstead for good. It became a community focal point again when the United Society purchased it and, under the leadership of James H. Brown, leased it to two Black fraternal organizations: Thames Lodge #2642, Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (G.U.O.O.F), and Jeptha Lodge #11 Prince Hall Affiliated F. & A.M. Both organizations provided support, fellowship and a gathering place for members who were barred from joining the all-white lodges of both the Odd Fellows and the Masons.

Thames Lodge #2642 was founded in 1885, shortly after the end of Reconstruction (1865-1877). This was the beginning of the Jim Crow era, and there was a clear need for unity and support in the face of rampant racism, bigotry, and discrimination. Fraternal organizations like the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows and Jeptha Lodge #11 Prince Hall Affiliated F. & A.M. stepped into the breach.

The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows’ mission statement speaks to their perception of the organization as a mutual aid society:

“. . . organized and created for the purpose of aiding and assisting each other, extending the helping hand to all in the time of need, uniting together for the common good of all, to promulgate and disseminate the true principles of friendship, love, and truth; preserve and diffuse the faith of the founders of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, and of society at large, as the embodiment of all the dictates of the human heart . . .”

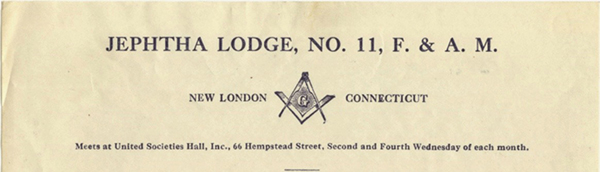

Jeptha Lodge #11 sign.

Jeptha Lodge #11 F. & A. M., as a Prince Hall Affiliate, voiced a similar mission: “The mission of the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons is to continue the legacy of making good men better through fraternal brotherhood, to aid and assist our widows, orphans, and distressed brothers, and to contribute to the community through service, scholarship, charity and training.”

The Prince Hall Masons are the oldest Black fraternal organization in America. The order was founded in the eighteenth century in Boston by Prince Hall, a leader of the Black community there, after his application for membership in the traditional white Masons was rejected because of his race.

Members of the Jeptha Lodge #11 laid the cornerstone for both the Shiloh Baptist Church and the Walls Clarke Temple A.M.E. Zion Church, the first Black churches to incorporate in New London.

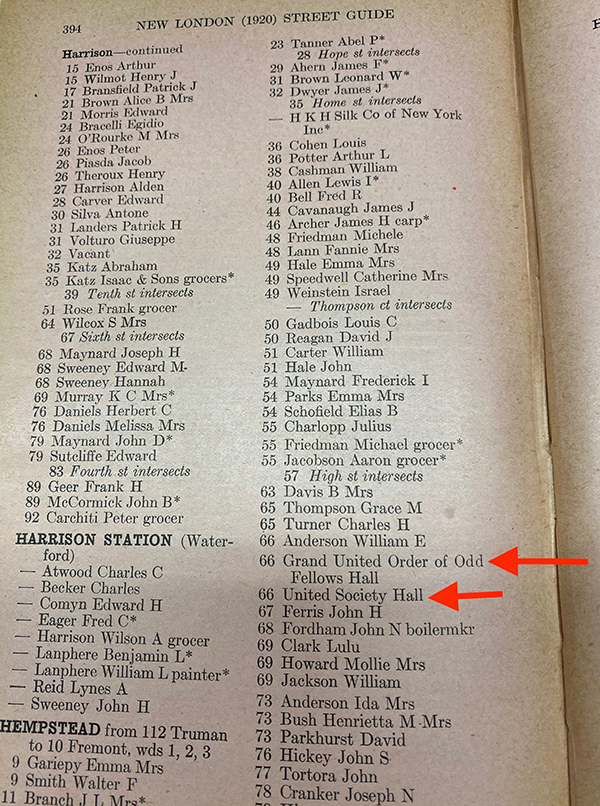

The 1914 New London City Directory lists 66 Hempstead Street as the home of the United Society, Inc., and 70 Hempstead as the Thames Lodge #2642 Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. James H. Brown is listed as the leader of both organizations. The 1920 City Directory identifies 66 Hempstead as the home of the United Society Hall. And by 1922, the Jeptha Lodge #11 F. & A. M., Prince Hall Affiliate is also listed at that address.

The Jeptha Lodge #11 purchased the building in 1944, and sold it in 2017 after relocating their headquarters to Stonington. As of 2021, it is privately owned and is in the process of being converted into apartments.

For more than eighty years, then, 66 Hempstead Street was the focal point of this vibrant Black community, hosting countless dances, banquets, family get-togethers and other social gatherings, in addition to the functions sponsored by its two resident Black fraternal organizations.

Over a span of one hundred and fifty years, 66 Hempstead Street was a place of joy and celebration, of spiritual growth and of community organization and support. It was a locus of unity and community for the Black families of New London. There is perhaps no better name for this building than the name it was known by in 1920: the United Society Hall.

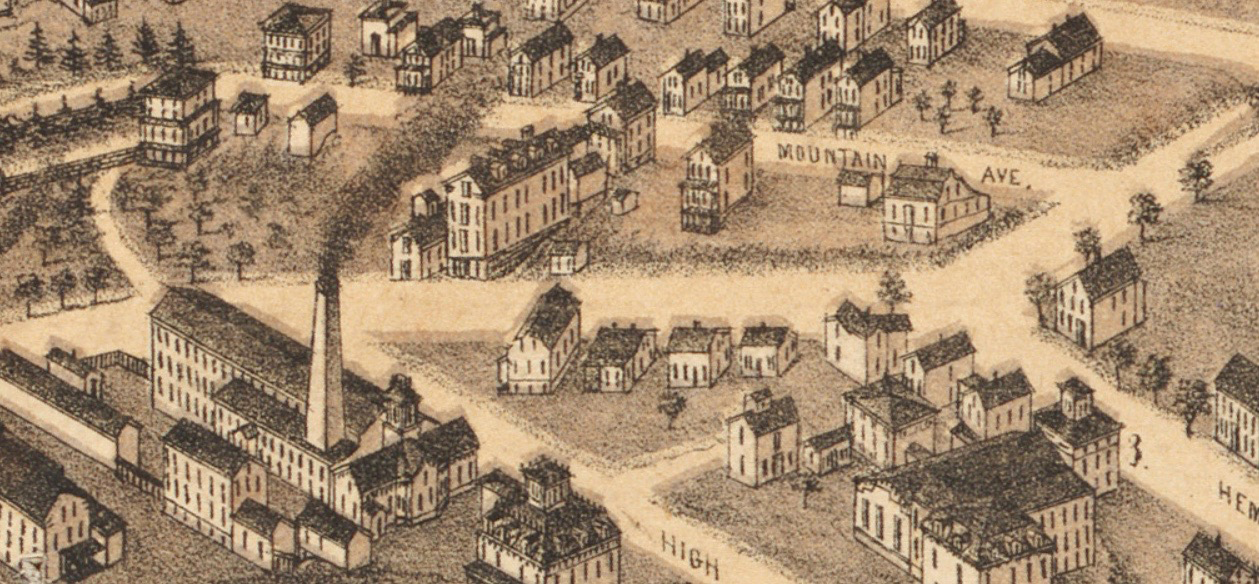

1876 map showing the Hempstead Street neighborhood.

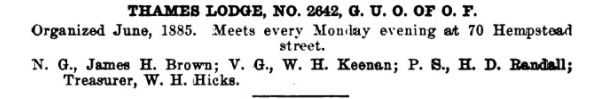

NL City Directory listing showing G.U.O.O.F. (Odd Fellows) meeting at 70 Hempstead Street circa 1920.

1929 NL White and Yellow Pages.

Jeptha Lodge #11 F. & A. M. letterhead circa 1922.

66 Hempstead Odd Fellows Hall United Society Hall 1920.