38 Green Street. Photo by Nicole Thomas.

38 Green Street

By Mary Beth Baker and Laura Natusch

Built in 1924, the Arthur Building at 38 Green Street in New London became a center of Black resilience and activism in the late 1920s, when it housed both the New England Peoples Finance Corporation (NEPFC) and the United Negro Welfare Council (UNWC).

The NEPFC and UNWC were linked by Sadie Dillon Harrison, who served as executive secretary to both organizations and whose half-brother, Benjamin Tanner Johnson, founded and managed the NEPFC.

The NEPFC and the UNWC were not the first Black-run institutions to make Green Street their home. Shiloh Baptist Church, Walls Clarke Temple AME Zion Church, the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows and the Jeptha Lodge #11 Prince Hall Affiliated F. & A.M. all held meetings on Green Street in the late nineteenth or early twentieth centuries.

United Negro Welfare Council

Negro Welfare Councils, in one form or another, could be found in many northern U.S. cities by the 1920s. Also known as Urban Leagues, they aimed to improve economic, social and cultural life for Black Americans, particularly for recent migrants from the Jim Crow South.

According to former New London NAACP president Linwood Bland, Jr.’s memoir A View of the Sixties: The Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut (2001), an early incarnation of New London’s UNWC, The Canteen, formed during World War I when community leader Elizabeth Jeter Greene organized a group of young Black women to assist Black soldiers stopping in New London. After the war ended, the group, now known as the UNWC, provided a social safety net for New London’s Black residents, helping with food, rent, utilities and other necessities.

According to former New London NAACP president Linwood Bland, Jr.’s memoir A View of the Sixties: The Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut (2001), an early incarnation of New London’s UNWC, The Canteen, formed during World War I when community leader Elizabeth Jeter Greene organized a group of young Black women to assist Black soldiers stopping in New London. After the war ended, the group, now known as the UNWC, provided a social safety net for New London’s Black residents, helping with food, rent, utilities and other necessities.

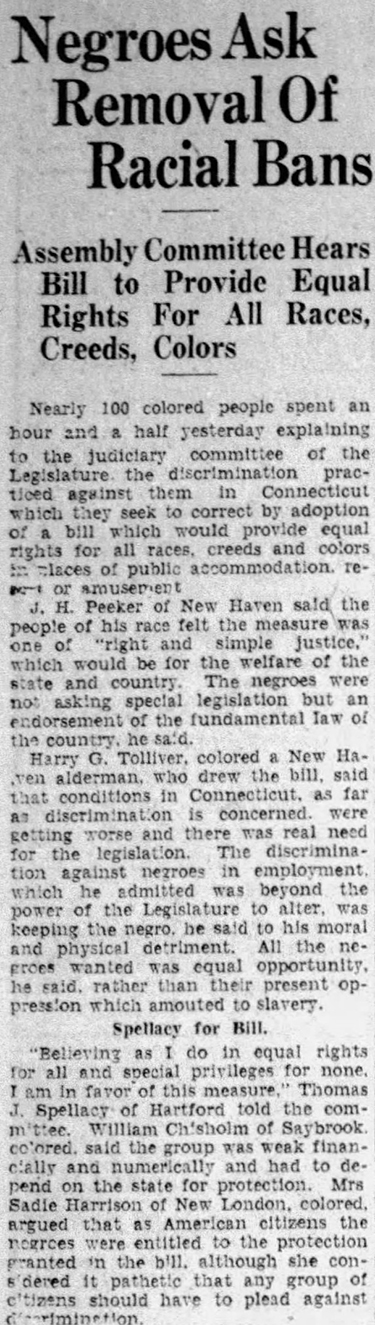

Although Bland describes the UNWC as providing tangible assistance for people in financial need, Harrison’s work indicates that the organization also championed civil rights. In February of 1927, she testified in Hartford in support of state legislation that would have prohibited racial discrimination in places of public accommodation, saying that although she considered it “pathetic” that anyone should still have to plead against racial discrimination, it remained necessary. Connecticut’s State Senate rejected the bill, which would have penalized violators with fines of between $100 to $500, jail time or both, on the advice of the Judiciary Committee, concluding that “present laws were adequate.” The following year, Harrison testified in court in New York State, stating that she and two other diners at a Southampton luncheonette were discriminated against when they were denied service at a vacant table and told they would only be served at the counter.

After Connecticut failed to pass the anti-discrimination legislation, Harrison, with the help of correspondents in over three hundred cities connected through the Welfare Council network, compiled a list of hotels and boarding houses where Black travelers would be welcome. She published the resulting directory with lawyer/poet Edwin Henry Hackley as Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers in 1930 and 1931. As Harrison pointed out in the book’s introduction, while she was compiling the directory W.E.B. Du Bois contacted her in her capacity as UNWC Secretary to ask where in New London he might find accommodations. He ended up staying at her house, 73 Hempstead Street in New London, which was listed in both her guide and in Victor H. Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book. Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Negro Travelers is the only known precursor to the Green Book, which it predated by seven years.

In 1928, the UNWC outgrew its headquarters at 38 Green Street and relocated a few blocks away to 39 Tilley Street. By the mid-1930s, Harrison had moved to Delaware for a job as superintendent of a school for Black girls. The Negro Welfare Council eventually changed its name to the New London Service League and changed its focus to serving disadvantaged youth. The New London Service League’s first president, Bennie McKissick Dover (later Bennie McKissick Dover Jackson) became the first Black substitute teacher in the New London Public School System in 1950 and the first Black full-time teacher in 1952.

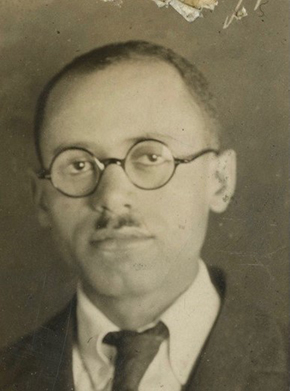

Benjamin Tanner Johnson

New England Peoples Finance Corporation

Harrison’s half-brother, Benjamin Tanner Johnson, moved to New London in 1927 from Canton, Ohio, where he had served as executive secretary to the Canton Urban League and from which he had fled the Ku Klux Klan, according to Johnson’s grandson, Dr. Kenneth Johnson. In 1928, he shows up in New London’s city directories living in Harrison’s house on Hempstead Street.

Johnson – a graduate of Howard University and the third Black graduate of Harvard’s School of Business – had been interested in forming a lending institution for Black entrepreneurs since the early 1920s. In January of 1922, he asked W.E.B. Du Bois for his support in starting a bank in Harlem, writing, “Are you willing to use your influence and money along with a few other conservative men – white and colored – toward helping to make a place in the commercial world for colored business America?”

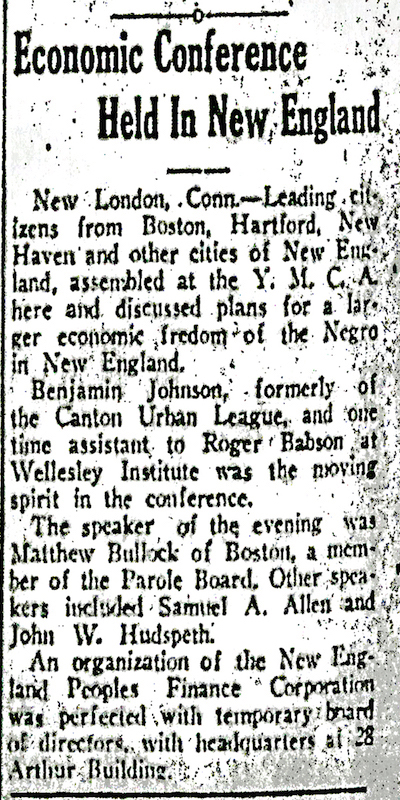

In New London, he was able to realize his dream of starting a lending institution to serve Black borrowers and investors. According to a December 10, 1927 article in the New York Age, Johnson was the primary organizer of a regional conference held at New London’s YMCA to discuss “plans for the larger economic freedom of the Negro in New England.” At the conference, attendees elected a temporary board of directors for the New England Peoples Finance Corporation.

Johnson managed the NEPFC in 38 Green Street until the organization’s closure in 1934. He then maintained a real estate office in the former NEPFC office for several years before joining the Works Progress Administration as a Connecticut state supervisor and the Social Security Board as a junior administrative assistant. In 1939, he left New London for opportunities in Boston. He later earned a law degree, taught finance at Howard University, and opened his own law firm.

Additional Information:

Full text of Hackley & Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers: Hackley & Harrison’s hotel and apartment guide for colored travelers – NYPL Digital Collections

Hartford Courant Feb 19 1927

Economic Conference Held in New England. New York Age, December 10 1927.