Sara Chaney

By Lonnie Braxton II

Sarah Chaney (2024). Photo courtesy of Lonnie Braxton II.

Sara Travis Chaney was born in Savannah, Georgia in 1935. When she was about five, her family moved from Savannah to New York City, where she attended and graduated from parochial school. Her life was shaped by the lessons she learned from her mother and grandparents, people of strong moral character and faith.

Ms. Chaney spent her childhood summers with her grandparents, Frank and Sarah Dobbins, at their home at 73 Hempstead Street in New London before moving in with them as a teenager. (Mr. Dobbins was a longshoreman who had been transferred from New York City to New London.) After graduating from high school in New London, she briefly attended Morgan State College in Baltimore, Maryland. While in college, she continued to spend summers in New London with her grandparents.

In the mid-1950s, Ms. Chaney helped form the New London branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). A family friend, Annette Hale, had attended an NAACP meeting in Hartford with the idea of forming a local branch. Ms. Chaney attended the first planning meeting at the Bulkeley School and participated in the membership drive along with Jacqueling Dell, Clarence Faulk, Spencer Lancaster, Rev. A. A. Garvin and others. Without their efforts, the New London Connecticut Branch of the NAACP wouldn’t have met the NAACP’s charter requirements. The branch received its charter on May 14, 1956, on the condition that it help further the NAACP’s objective “to uplift the Colored men and women of this country by securing to them the full enjoyment of their rights as citizen’s, justice in all courts, and equality of opportunity everywhere.”

Ms. Chaney also met her future husband, Alvan Chaney, in New London. They married here on April 1, 1956. Following her marriage, Sara did not return to Morgan State. She and Alvan had three children: Alvan Jr., Arthur, and Von Eric. After their marriage ended in divorce, she found employment at Chase Manhattan Bank in New York City, a job which led to her breaking the color barrier in New London’s banking industry.

Sara Chaney (seated) with Gwen Braxton. Photo courtesy of Lonnie Braxton II.

In 1961, Hartford National Bank and Trust’s New London branch advertised in The Day for a bookkeeper with experience operating a Burroughs machine. The ad caught the attention of Mr. Linwood Bland, Jr., who was then president of the New London branch of the NAACP. Over the years, Mr. Bland had made it his mission to ensure that all local jobs were open to all qualified applicants, and he knew that Hartford National Bank and Trust’s New London branch neither hired nor interviewed applicants of color.

Mr. Bland also knew that Ms. Chaney was operating a Burroughs bookkeeping machine at Chase Manhattan Bank in New York and that, given her ties to New London, she would be happy to relocate here. He contacted her and encouraged her to apply for the position.

After submitting her application, Ms. Chaney waited for weeks to hear back from Hartford National Bank. Eventually she spoke with a bank representative who told her that she would have to travel to Hartford for her interview. This struck both her and Mr. Bland as odd because they were well aware that the bank’s New London branch conducted all of its interviews locally. Nonetheless, she complied and traveled to Hartford to be interviewed.

Ms. Chaney left the interview believing that she had secured the position pending a reference check. She submitted her notice at Chase Manhattan and began making arrangements to move to New London. But as she approached her final day at Chase Manhattan without having received a job offer, she asked Chase Manhattan’s personnel office if Hartford National Bank had called to check her references. They had not. Aware of the bank’s discriminatory hiring practices, she realized that the job had fallen through and she was about to be unemployed.

In 1961, Sara Chaney responded to an advertisement for a Burroughs machine operator at Hartford National Bank. The Day, Sept 16, 1961.

What was she to do? With support from Mr. Bland and the New London branch of NAACP, Ms. Chaney decided to fight. She traveled to Hartford National Bank’s headquarters in Hartford and filed a complaint.

Not only did her complaint result in her being hired by Hartford National Bank, but it changed hiring policies throughout Connecticut’s banking industry. Hartford National Bank revised its hiring policies for all of its branches, as did other banks with discriminatory policies. In a recent interview, when asked what her happiest moment during her employment at the Hartford National Bank had been, Ms. Chaney replied, “Seeing other people of color being hired.”

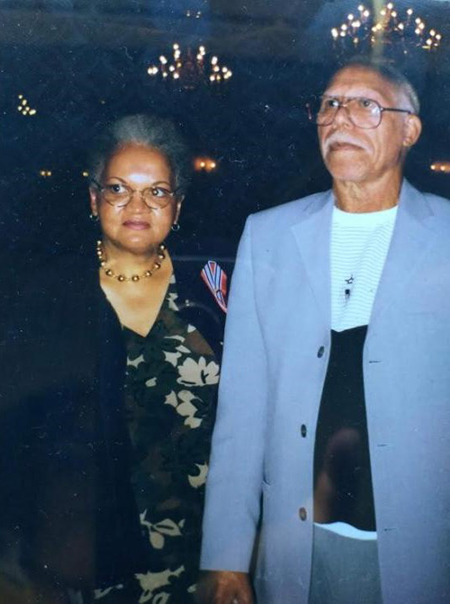

Sara Chaney with Linwood Bland, Jr. Photo courtesy of Lonnie Braxton, II.

In 1973, Ms. Chaney left Hartford National Bank for a job that offered better pay, benefits and opportunities at General Dynamics Electric Boat. When she was hired, she was one of very few women employed in the actual shipyard where the submarines were being built. Women were not particularly welcome in the docks area of the shipyard—and Black women even less so. But whenever she encountered racism or sexism at Electric Boat, she did not let it pass unchallenged.

Ms. Chaney’s belief in fair play and a level playing field for everybody in the shipyard did not go unnoticed. She was appointed to or was asked to participate on many union and Industrial Relations Department committees. Her unwavering belief in justice and equality served her well during the twenty-seven and a half years she worked at Electric Boat before retiring in 2000. Her stance, along with that of other community leaders such as the Rev. Albert Garvin and Linwood Bland, Jr., was instrumental in creating not only a better work environment, but also a more inclusive and just society for all. Her involvement with United Way and union affairs–especially their community outreach programs such as the Gemma E. Moran United Way Labor Food Center–speaks volumes about her love for humanity.

Throughout her life, Ms. Sara Chaney has maintained her commitment to making this a better world, not just through talk but through her actions. She can always be found supporting causes she believes in. And if there is one request that you are sure to hear her make, that request is, ‘PLEASE VOTE because it matters, and if you want to matter, you had better vote.”

Note: This essay is based on multiple conversations between Sara Chaney and Lonnie Braxton II in early 2024.

From left to right, Sara Chaney, Bennie Dover Jackson and Jean Jordan.